Are Top US Universities Really so Bad at Research?

QS reports Yale, Chicago, NYU, are terrible for citations

In a recent newsletter, I discussed the relative decline of some American universities in the most recent edition of the QS World University Rankings. That was partly due to the recovery of Asian universities from a temporary downturn resulting from QS’s introduction of three new indicators. It is also likely that they faced issues with QS’s citations per faculty indicator.

Universities tend to get overexcited about changes in popular rankings like QS and Times Higher Education (THE). One common reaction is to try to influence metrics related to faculty student ratio (FSR), which can be found in world and regional rankings published by QS, THE, and Round University Rankings. This is a tempting choice since it can be put into effect more quickly than recruiting or training faculty who may eventually write papers that may eventually produce citations, or by patiently cultivating a reputation for research or teaching excellence.

But it is not a good idea. Faculty student ratio can be improved in two ways: by reducing the number of students reported to the rankers or by increasing the number of faculty. The first approach would surely be opposed by faculty and administration, as it would reduce revenue and, more importantly, the justification for employing faculty. Increasing the number of faculty reported would reduce the scores for the various metrics where faculty is the denominator.

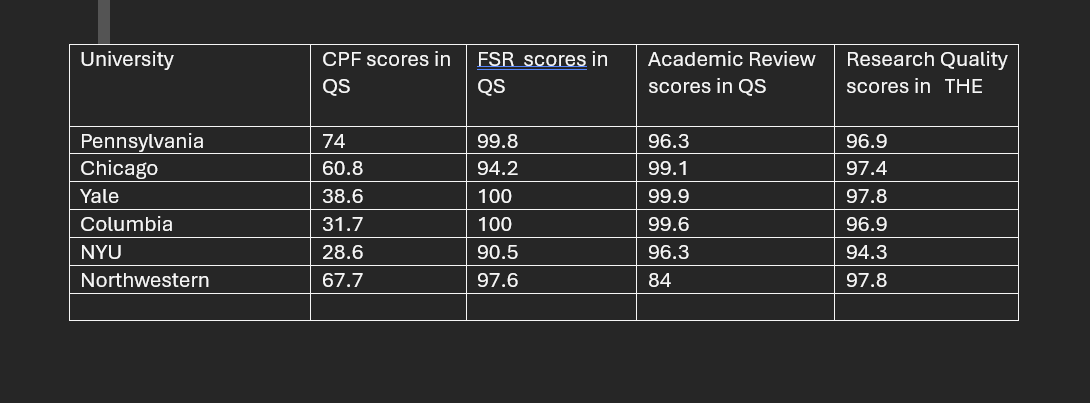

Getting to the title of this piece, if we look at elite US universities in the most recent QS world rankings, some of them have very low scores for citations per faculty. The scores of the six universities in the table below for Citations per Faculty are mediocre or worse, ranging from 74 for Pennsylvania to 28.6 for New York University. (The top university for the indicator gets 100.)

Normally, we would expect universities like those to be scoring in the 90s, as do their national and international peers like MIT, the National University of Singapore, Melbourne, Princeton, Amsterdam, and Carnegie Mellon. The incongruity is increased when we examine the scores for academic reputation, which are assessed by a survey of researchers. It is normal for respondents to vote for those universities whose researchers they cited. But five of those universities are scoring in the nineties for academic reputation, and the lowest, Northwestern, scores 84.

We can also examine the THE scores for citations, where universities are scoring in the nineties. THE has a different kind of indicator, using field-weighted citation counts as the heart of its system, so we should not expect the two scores to be exactly the same. Even so, these universities are scoring high for citations in both rankings.

Anyway, to get to the point, the clue seems to lie with the FSR metric, scores for which are significantly higher than the scores for citations. Indeed, Yale and Columbia get the highest possible scores of 100.

The FSR score is calculated by dividing the number of faculty by the number of students. The citations score is citations divided by the number of faculty. So, the larger the number of faculty submitted by universities to QS, the better the FSR score and the lower the CPF score.

QS used to discount the possibility of universities improving their FSR scores by inflating the number of faculty they submitted, noting that an improvement in the FSR score would be matched by a decline in that for citations. That was not strictly true. If a university were scoring in the high nineties for FSR, adding more faculty would bring only a marginal increase, but it could reduce the CPF score if the university were in the middle range there.

But two years ago, QS dropped the weighting for the FSR metric from 20% to 10%, so that it was now much to the advantage of universities to make sure that their faculty numbers were kept as low as possible in order to maximise their scores. I do not want to get into individual cases here, but I wonder whether these universities have focused on recruiting or reporting the number of staff to improve their standing in the rankings, a move that has backfired by bringing down their scores for Citations per Faculty.

Whatever the exact individual circumstances, it seems that these universities need to take a close look at the faculty data they have submitted to QS and maybe other rankings and see if they can be adjusted.