Science moves East

Digging into the Shanghai Rankings

The Shanghai rankings (ARWU) started over two decades ago. Their methodology is straightforward and simple compared to the complexity and opacity of the THE world rankings and their various offspring, but they can tell us a lot if you ask the right questions.

The latest edition of the rankings, released last week, shows at first sight a comforting story, one that might gladden the hearts of the American and European elites. Looking at the overall rankings, Harvard is in first place, as it has been since 2003, followed by Stanford and MIT. The UK is doing well with three institutions, Oxford, Cambridge, and University College London, in the top twenty. Continental Europe lags behind a bit, but its best performer, Paris-Saclay, comes in at thirteenth place. Then there is ETH Zurich holding up in 21st place.

Here we have a typical response from Université Paris-Saclay.

“On 15 August 2025, ShanghaiRanking Consultancy published its Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU). Ranked 13th in the world, and the leading university in France and Continental Europe, Université Paris-Saclay has once again confirmed its position as a world-class research intensive university.”

But the Shanghai rankings have in effect become two different rankings under the same label. The Alumni indicator counts Nobel and Fields award winners going back to the 1920s, and the Award indicator counts faculty winning those awards as far back as the 1930s. Unsurprisingly, these are a record of the research prowess of universities going back a century, although they are weighted towards recent years.

There is another indicator, PUB, that counts the number of articles indexed in the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Social Science Citation Index in the year preceding the publication of the rankings. For the latest rankings, that was 2024. There is, of course, a time lag between the start of a research project, the processing of grant proposals, the conduct of research, composition, submission, review, and so on, but this indicator is a reasonably current assessment of the research capabilities of universities.

It is, admittedly, not a perfect one since it does not take account of research in the humanities, nor does it consider innovation, teaching, progress towards sustainable development goals, or any of the amazing things that universities are supposed to do.

Looking a bit closer, we can see that the indicators are beginning to diverge. The correlation between alumni and publications for the whole dataset of 1000 universities is very modest, 0.36, and for Awards, it is 0.35.

However, when examining the top 200 universities in these rankings, no correlation is found between Alumni and Publications. The correlation for the first pair is 0.01, and for the second, it is -0.04.

Let’s pursue this point a little bit. There is effectively no link between the prizes and medals won by universities over the last century and their contemporary capability for scientific research.

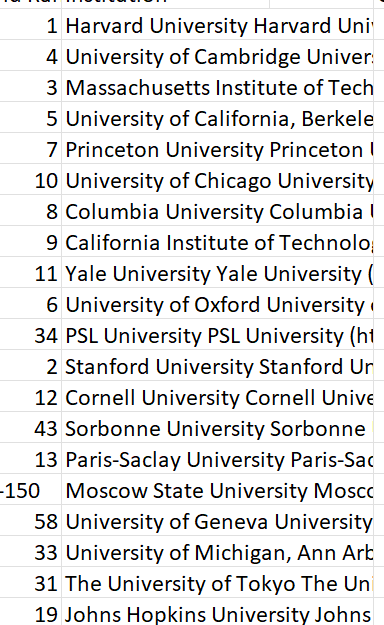

Here we have a screenshot of the top twenty for Alumi in the 2025 Shanghai Rankings published last week. It looks very much like a snapshot of the research world around 1950 or 1960.

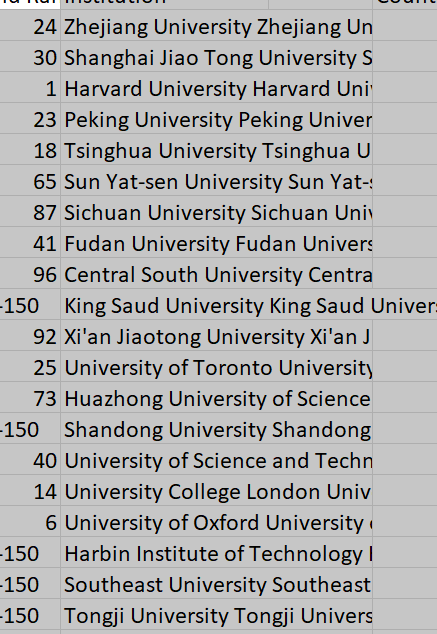

Then we have the top twenty for publications.

This looks like the research world as it might be in 2030 or 2040. Chinese schools, including many that most people in the West have never heard of, are in the lead. Harvard is still doing well, but I think I can safely predict that it will continue to decline for the foreseeable future. Then we have King Saud University coming in at number 10, and the University of Toronto, UCL, Oxford, Johns Hopkins, São Paulo, and Seoul National University.

As for the more distant future, it is wise, as Wayne Rooney is supposed to have said, not to make predictions, especially about the future, but it would be a good bet that there will be very few Western universities among the world’s research elite in another two or three decades. Except among Nobel and Fields laureates, if they are still in existence.